A synthetic overview

Abstract: A synopsis of the current scholarly knowledge of the Bevel Rimmed Bowls. Description, production methods, distribution and potential functions.

Keywords: Bevelled Rimmed Bowls, Bevel Rimmed Bowls, BRB, Uruk, bevel-rim bowl, bevelled-rimmed bowls, Mesopotamia, Iran, Ancient Near East, Archaeology, ration bowl.

Introduction

One interesting puzzle found within material culture of Greater Mesopotamia is the notorious Bevel Rimmed Bowl (BRB). These BRBs have been deeply rooted in scholarly discussions for years in regards to their function and their place in Uruk Mesopotamia society. Though still unknown, new archaeological forms of analysis have helped to present a better understanding of these BRBs. This paper is designed to give a synthetic overview of the scholarly understanding and knowledge of these Bevel Rimmed Bowls.

Through the use of formal descriptions, production methods, the proposed function of the bowls and, the distribution of BRBs across Mesopotamia and Iran, I will present a synopsis of the state of research of the BRBs with the intent of stimulating future research on these enigmatic vessels. The Bowls are a phenomenon of the Uruk period of Mesopotamia, c. 3900-3100 BCE, with their peak of abundances occurring in the mid-to-late 4th mil. BCE (Potts, 2009, p.1, Goulder, 2010, p. 352).

Found within the Uruk Period the BRB was an innovation of the Uruk culture (Millard, 1988, p. 55). Jill Goulder has created a table with a more accurate timeline of the BRB and its role within Mesopotamian society (Goulder, 2010, p. 351). (See Table 1 for Goulder’s in-depth BRB timeline).

Description

These BRBs are ceramic bowls that have distinctive coarse and thick walled conical shapes with flat bases (Goulder, 2010, p. 351). The clay of the bowls is heavily tempered with chaff and lightly fired, giving the vessels a porous outer texture (Millard, 1988, p. 49). They are usually about 10 cm in height and 18 cm in diameter. The interior walls of the bowls are more smooth, and they possess a trimmed or bevelled rim, indented, this feature being responsible for their description, “bevel rimmed” (Millard, 1988, p. 49-50). (See figure 2 for Millard’s comparison of BRBs to other common tableware of the period). The BRB has been described as ‘mud-ware’, ‘earthenware’ and ‘badly fired pottery’ because of the bowls’ outer porous texture and their coating of fine grained clay-slip on the inside (Millard, 1988, p. 51). Given their rough fabric, Millard suggests that the bowls are too grainy and porous to be regarded with a traditional ‘tableware concept’ of finery (Millard, 1988, p. 51). This non-tableware idea is supported by Nicholas who suggests that the BRB could be classified as a ‘special container’ (Nicholas, 1987, p. 65).

Thomas W. Beale did extensive studies of the capacity of the BRBs and found that most of the bowl sizes had carrying capacities between 0.4 and 0.95 litres (Beale, 1978, p. 290). Because Beale found that there was considerable variety in the capacity of the bowls from site to site, he concluded that that there was no standardized bowl capacity (Beale, 1978, p. 293). (See figure 3 for Beale’s formulas for calculating BRB volumes). Beale, referencing Johnson, suggests that the lack of uniformity in the bowls’ carrying capacity could imply that no care was given to the accuracy of the bowls’ size, implying a multi purpose use (Beale, 1978, p. 295). The capacities of the BRBs were not a factor in their production and Beale brings forth the idea that the inaccuracies in sizes could be due to the vast distribution over various areas of Greater Mesopotamia and the contexts in which the bowls were found (Beale, 1978, p. 292, 300).

Methods of Production

There are many interpretations as to how the BRBs could have been made. One production method is proposed by J. Karlsbeck, who suggests that a BRB was built out of a lump of clay in the hand and then possibly pinched with fingers and moulded into shape without a template (Chazan & Lehner, 1990, p. 25). Also noteworthy are the finger or fist marks on the bottom of the inside of the bowl. These impressions were noticed by Karlsbeck in 1980, who argued, that the BRB was formed by hand (Goulder, 2010, p. 352). However Chazan and Lehner point out that there are often joining lines down the inside of the bowl, which could indicate that the bowls were made out of separate pieces that were joined together (Chazan & Lehner, 1990, p. 25).

Beale suggests that they were formed by moulds dug into the ground (Beale, 1978, p. 289). His reasoning for this is that the moulded earth is more practical because it allows the maker to accurately predetermine a bowl size and shape which makes the reproduction faster (Beale, 1978 p. 299). Jill Goulder’s experimental archaeology determined that this ground-moulding method was too tricky and very time consuming for forming a straight side and flat base (Goulder, 2010, p. 352-353). On the basis of her experiments, she concluded that ground moulding on a mass scale would have been impractical and would have taken too long to dry (Goulder, 2010, p. 353).

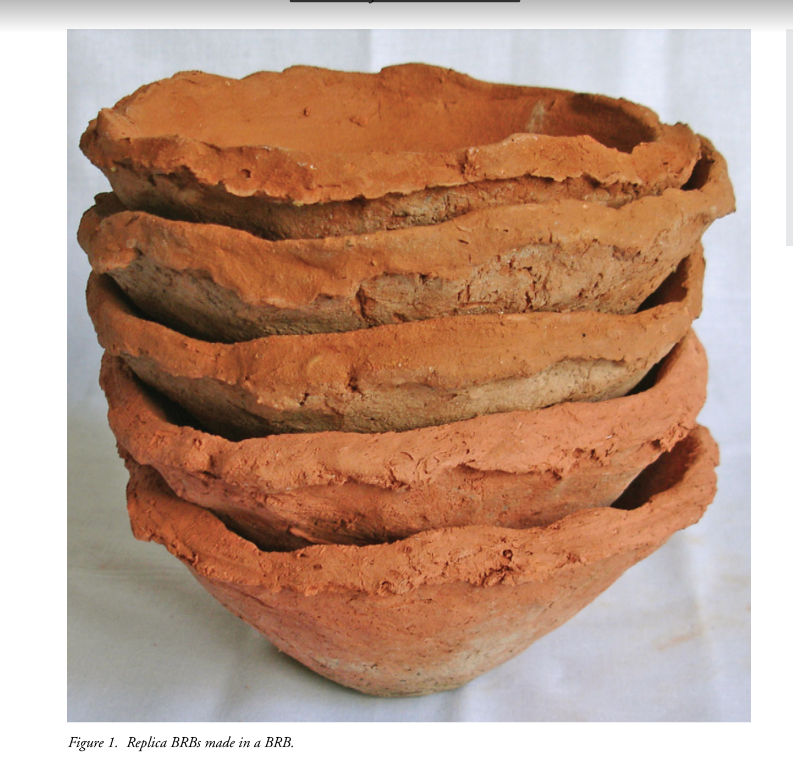

An alternative proposal has been put forward by Millard who has suggested that BRBs were made using an older bowl as a template (Chazan & Lehner, 1990, p. 25) and indeed Algaze has found convincing evidence to suggest that at Arslantepe, an older BRBs were used as templates in the reproduction of new BRBs (Algaze, 1993, p. 67). Goulder, Chazan, Lehner and Bill Sillar also agree with this method and Goulder notes that in her experiment, BRB-making was very successful because the clay moulded well to the already defined walls of the template, and the clay raised over the edge to create the rim (Goulder, 2010, p. 353).

older bowl (Goulder, 2010, Figure 1, pg. 353).

Millard also noted finger mark imprints into the base of the bowls (Millard, 1988, p. 50). Goulder states that she experimented with this construction style and found that it required too much effort to create the straight sides and flat base by hands alone (Goulder, 2010, p. 352). Goulder, suggestions of Adams, Batfet, Forest, Charvat and Crawford who wondered if the bowls were moulded from “a free-standing mould” presumably made out of wood (Goulder, 2010, p. 352). Through her experiments, she reported that using “a free-standing mould” made the process more convenient initially, and helped in the bevelling of the rim (Goulder, 2010, p. 353). This is Goulder’s preferred method (see figure 5 for her replicated BRBS) because the use of an older bowl as a mould allowed her to create replica bowls in a short amount of time which was practical and easy to produce (see table 2 for Goulder’s summary of methods and experiments).

The last important discovery from Goulder’s experiments determined that wheel-based production was not a viable method. The speed and successful output of wheel production was only as good as the experience of the potter and the poor to moderate quality of the BRBs and their cheap materials suggests that they were not made by highly skilled workers (Goulder, 2010, p. 355). (See table 3 for summary of methods of production).

Proposed Function

Distribution across Mesopotamia

Distribution across Iran

Bibliography

Algaze, Guillermo (1993). The Uruk World System: The dynamics of expansion of early Mesopotamian civilization. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Beale, Thomas Wright (1978). Bevelled Rim Bowls and their Implications for Change and Economic Organization in the Later Fourth Millennium BC. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 37 (4), 289-313. https://www.jstor.org/stable/544044

Beale, Thomas Wright (1978). Formulas for calculating BRB volumes [Drawing]. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/544044

Berman, Judith C. (1989). Neutron activation analysis of beveled rim bowls and other Uruk ceramics from the Susiana Plain, Southwestern Iran. Paléorient, 15, 289-290. https://www.persee.fr/doc/paleo_0153-9345_1989_num_15_1_4955_t1_0289_0000_3

British Museum. (2018). Bevel Rimmed Bowl, acquired 1919 [Photograph].

Retrieved from:

https://www.britishmuseum.org

Buccellati, Giorgio (1990). Salt at the Dawn of History: the case of the Bevelled-Rim Bowls. In P. Matthiae, M. Van Loon & H. Weiss (Eds.), Resurrecting the Past: A Joint Tribute to Adrian Bounni, (pp.17-40). Leiden: Nederland Historisch-Archaeologisch Institut te Istanbul.

Chazan, Michael & Lehner, Mark (1990). An Ancient Analogy: Pot Baked Bread in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Paléorient, 16 (2), 21-35. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41492418

Forest, J-D. (1987). Les bevelled rim bowls. Nouvelle tentative d’interprétation. Akkadica, 53, 1-24.

Goulder, Jill (2010). Administrator’s bread: an experiment-based re-assessment of the functional and cultural role of the Uruk, bevel-rim bowl. Antiquity, 84, 351-362. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X0006662X

Goulder, Jill (2010). Approximate timelines of the BRB [Table].

Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X0006662X

Goulder, Jill (2010). Goulder’s experimental archeology, replica of BRBs made from an older bowl [Photograph].

Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X0006662X

Goulder, Jill (2010). Goulder’s summary of methods and experiments [Table]

Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X0006662X

Mayyas, A., Stern, B., Gillmore, G., Coningham R., Fazeli Nashli, H. (2012). Beeswax preserved in a late Chalcolithic bevelled-rim bowl from the Tehran Plain, Iran. Iran, 50, 13-25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24595836

McMahon, Augusta (2005). From Sedentism to States, 10,000 – 3000 BCE. In Daniel C. Snell (Eds.), A Companion to the Ancient Near East (pp. 20-33). Blackwell Publishing.

Millard, A.R. (1988). The Bevelled-Rim Bowls: Their Purpose and Significance. Iraq, 50, 49-57. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4200283

Millard, A.R. (1988). Example of a bevel rimmed bowl [Drawing].

Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/4200283

Nicholas, Ilene M. (1987). The Function of Bevelled-Rim Bowls: A Case Study at the TUV Mound, Tal-e Malayan, Iran. Iran, 13, 61-72. https://doi.org/10.3406/paleo.1987.4429

Nissen, Hans J. (2015). Urbanization and the techniques of communication: the Mesopotamian city of Uruk during the fourth millennium BCE. In Norman Yoffee (Ed.), Part II – Early cities and information technologies (pp.113-130). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139035606.009

Oriental Museum Chicago. (2018). Bevel Rimmed Bowl [Photograph].

Retrieved from: http://teachmiddleeast.lib.uchicago.edu/historical-perspectives/empires-to-nation-states/before-islam/image-resource-bank/image-03.html

Pollock, Susan (2012). Politics of food in early Mesopotamia centralized societies. ORIGINI 34, 153-168.

Postgate, J.N. (2010). The Debris of Government: Reconstructing the Middle Assyrian State. Iraq, 72, 19-37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20779018

Potts, Daniel (2009). Bevel-Rim Bowls and Bakeries: Evidence and Explanations from Iran and the Indo-Iranian Borderlands. Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 61, 1-23. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25608631

Sanjurjo Sanchez, J., Montero Fenollos, J.L (2012). Restudying the Beveled Rim Bowls: new preliminary data from two Uruk sties in the Syrian Middle Euphrates. Anti, 3, 263-277. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269695265

Stephen, Fiona M.K. & Peltenburg, Edgar (2002). Scientific Analyses of Uruk Ceramics from Jerablus Tahtani and Other Middle-Upper Euphrates Sites. In J.N. Postgate (Ed.), Artefacts of Complexity: Tracking the Uruk in the Near East, (pp. 173-179). Wiltshire, England: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, and Aris and Phillips Ltd.

Ur, Jason (2014). Households and the Emergence of Cities in Ancient Mesopotamia. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 24 (02), (249-268). https://doi.org/10.1017/S095977431400047Xq

~ Larissa Luecke